Why a world-class resource is no longer enough – and what this means for investors deciding between Chile, Argentina and the rest of the lithium map.

Chile’s lithium story is often told as a domestic debate about royalties, institutions or political cycles. For investors and strategic decision-makers, the real issue is simpler – and more uncomfortable: Chile is no longer the structural cost leader in a market it helped build.

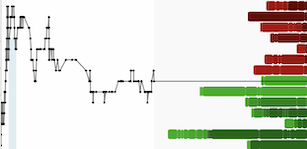

For almost two decades, the Atacama basin combined Tier-1 brine, institutional stability and highly competitive costs. That combination turned Chile into the anchor of global lithium supply and a “default jurisdiction” for many portfolios. Today, the data tells a different story. On S&P’s 2024 cost curves, Chile sits closer to the top than to the bottom, even as Australia, Argentina and China expand capacity at speed.

The question is no longer whether Chile has the right geology. It is whether its system can still turn that geology into durable advantage.

From cost leader to cost laggard

The shift is most visible on the cost curve.

In 2000, Chile sat among the lowest-cost lithium producers globally. Total cash costs for lithium carbonate hovered around US$1,155/LCE – comfortably below Australia, Zimbabwe, the U.S. and most emerging producers.

By 2024, the picture had changed dramatically. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, Chile’s cash costs for lithium carbonate reached around US$8,253/LCE, and hydroxide costs around US$10,348/LCE – placing the country among the highest-cost producers internationally. Chile is now more expensive than Zimbabwe, Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, China and the U.S., despite having one of the world’s most competitive brine resources.

This is not a cyclical story of prices or a temporary squeeze. It is a structural story about governance, technology, hydrology and volume.

How did Chile get here?

Chile’s lithium framework is not an accident of recent politics. It is a legacy of an earlier geopolitical era.

During the Cold War, lithium was formally classified as a “material de interés nuclear” and placed under the authority of the Chilean Nuclear Energy Commission (CCHEN). The same architecture designed to regulate radioactive materials ended up shaping the governance of lithium. Over time, that security-driven model layered new institutions and contracts on top, but was never fully adapted to the demands of a fast-moving, technology-driven battery economy.

For investors, this legacy shows up in five ways:

1. Fragmented governance with too many veto players

Corfo, CCHEN, the Ministry of Mining, the Ministry of Environment, Codelco, ENAMI and regional authorities all play a role. What used to take months now takes years. Overlapping mandates generate uncertainty not only for new capital, but even for operators already in production.

2. Royalty structures that push Chile up the cost curve

Chile’s royalty framework, renegotiated over time and indexed to price, delivers high fiscal take in boom cycles – but structurally raises unit costs compared to Argentina’s provincial regimes or Australia’s hard-rock royalties. For a while the Atacama’s quality masked that effect. It no longer does.

3. Technological stagnation in extraction

While other jurisdictions are experimenting with direct lithium extraction (DLE), hybrid evaporation systems and new brine chemistries, Chile has moved slowly. Continued reliance on legacy evaporation infrastructure has eroded yields and increased exposure to operational risk and cost volatility.

4. Hydrological uncertainty in a stressed basin

Atacama is a hydrologically sensitive system. Without a basin-wide water model, companies face conservative extraction limits, additional monitoring requirements and higher operational risk. These safeguards are legitimate – but in the absence of better data and integrated governance, they translate into structural inefficiencies.

5. Plateauing and declining volumes

As Australia, Argentina and China added capacity, Chile’s output flattened and even contracted in certain periods. Lower throughput inevitably pushes unit costs higher, particularly in high-fixed-cost systems.

The result is that Chile’s advantage is no longer structural.

The country still has world-class geology. What it no longer has is an unquestioned cost position or an unquestioned system.

Three futures in the Lithium Triangle

Chile’s story doesn’t exist in isolation. Investors are not choosing between Chile and “nowhere”; they are choosing between Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and other fast-scaling jurisdictions.

A simple way to frame the Lithium Triangle is as three models and three futures:

Argentina – Expansion at speed, stability in debate

A federal, province-driven model that has become the most dynamic lithium frontier in the world. Dozens of salares are moving through exploration, construction and commissioning, supported by relatively investment-friendly policies compared to its neighbours.

The October 2025 elections gave President Javier Milei a renewed mandate for a pro-market, deregulation-oriented agenda, providing greater political backing to push reforms and implement processes that had long been discussed but not executed. The opportunity is a faster alignment between rhetoric and policy on investment and trade. The risk is that macro instability, currency volatility and regulatory asymmetry between provinces still undermine the system just as scale is achieved.Bolivia – Geological scale, institutional constraint under a new leadership cycle

Bolivia holds the largest theoretical lithium resources, concentrated in Uyuni, but limited technological scalability, centralised governance and political uncertainty have kept production well below potential. For two decades, a state-dominant model and restrictive laws deterred foreign capital and slowed technology transfer.

The election of Rodrigo Paz in late 2025 opens a new political chapter, with a discourse that explicitly distances itself from the Evo Morales era and signals an interest in revisiting how Bolivia engages with markets and foreign partners. For now, however, the core constraints remain: the legal framework has not yet been fully updated, social tensions in Potosí are unresolved, and brine chemistry is still complex to process at scale. Bolivia therefore remains the clearest example of a core theme in geopolitical mining: without an industrial system, geological potential remains unrealised potential.Chile – Mature coalitions, emerging pressures in a new electoral test

Once the uncontested benchmark for predictable rules and Tier-1 brine, Chile now faces governance fragmentation, rising royalties, slower technology adoption and declining volumes. On top of these structural pressures, the country is heading into a presidential runoff between Communist Party candidate Jeannette Jara — broadly seen as continuity with the Gabriel Boric administration — and José Antonio Kast from the Republican Party, who proposes a more market-oriented shift in economic policy and the role of the State.

Their contrasting views on public companies, regulation and foreign investment in strategic sectors will shape the next phase of Chile’s lithium policy. Chile remains a heavyweight in lithium, but its influence now depends less on its resource and more on whether the next administration can rebuild a coherent system, rather than relying on its institutional past.

From an investor’s perspective, the trade-off is no longer “Chile = safe, others = risky”. It is a portfolio question: How much exposure to a high-quality but slower system versus faster, more volatile frontiers?

The Codelco–SQM deal: signal or solution?

In this context, the Codelco–SQM partnership has been widely interpreted as a decisive turning point. In reality, it is better understood as a necessary rebuilding step, not a solution in itself.

Bringing Codelco into a long-term joint venture can:

stabilise production in Atacama,

give the State a clearer strategic role,

and provide a platform for technological upgrades and midstream partnerships.

But even the best-designed JV will not fix structural issues unless:

governance is simplified,

basin-level hydrological data is integrated and credible,

permitting becomes predictable,

reinvestment incentives are aligned, and

technology adoption is accelerated.

For capital, the relevant question is not “Is Codelco–SQM good or bad?” but:

“Does this arrangement sit inside a system that is evolving, or inside a system that remains structurally constrained?”

What this means for investors and boards

For investors and boards, the decision is not whether to engage with Chile. The country still offers:

proven Tier-1 brine,

experienced operators,

deep institutional knowledge,

and a central position in global lithium contracting.

The decision is how to engage – and on what assumptions.

Three practical implications:

Price Chile as a system, not just a resource

Cost curves, permitting timelines and hydrological constraints are now as important as grade and recovery. Chile is no longer a “safe default”; it is a complex, high-potential system that requires active monitoring.Benchmark Chile against Argentina and Australia on execution, not geology

Portfolios concentrated in Chile should be stress-tested against scenarios where Argentina overtakes it in volume and Australia continues to expand hard-rock supply at speed. The question is how Chile’s system performs under those competitive pressures.Watch the next decade of reforms, not just the next year of headlines

A 10-year national strategy for critical minerals, unified lithium governance, basin-level data, redesigned permitting and midstream/value-capture policies will determine whether Chile restores its leadership – or gradually becomes a slower, higher-cost jurisdiction in a market that rewards speed and integrated systems.

In Mining Is Dead. Long Live Geopolitical Mining, we argue that sovereignty in critical minerals is industrial, not rhetorical. It belongs to the countries that turn geological privilege into systems: governance, technology, midstream capacity, credible rules.

Chile still has the opportunity to do exactly that. But for investors and boards, the era of assuming that Atacama’s geology automatically guarantees structural advantage is over. The next phase will be decided not by the quality of the resource, but by the quality – and speed – of execution around it.