Written by Peter Bell on September 12, 2025 for the Munich Personal RePEc Archive:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1oT6lhe2nL7kWlP03dCjnpkiJh4c3FMWyLdkSp3fpjeA/edit?tab=t.0

Abstract

This paper shows ways to simulate financial economic models for a mining exploration company. Two types of data are used: a time series of annual financial statements for a particular company and the stock exchange listing requirements for mining exploration companies in general. I describe how Kermode Resources Ltd.'s audited financial statements reflect different eras of leadership within the company over time and show how key corporate costs can vary as leadership and strategy change. I show a toy model of the costs of running a public company based on the constraints from the TSX Venture Exchange as a hypothetical company running on the edge of the listing requirements. I compare the bare-minimum cost profile of the hypothetical company under the listing requirements with similar corporate costs observed in Kermode Resources' financial statements over time.

Keywords: Engineering Economics, Mining, Royalties, Finance

JEL Codes: C00 General; G00 General; L72 Mining, Extraction, and Refining

Counterfactual Simulation of Corporate Costs for Public Companies

My article (Bell, 2014) shows a method for simulating time series data in situations where there are regime shifts in foundational economic parameters. It is possible to apply this concept to the financial statements of a single company. For example, Kermode Resources Ltd. has reported the audited annual financial statements for more than twenty years. There are nuances in this data that reflect at least two regimes.

My article (Bell, 2025a) presents basic models of how leadership strategies are reflected in Kermode’s financial statements. My article (Bell, 2025b) presents the range of valuations for mineral deposits based on a global geological database. It simulates economic returns to exploration, making simplifying assumptions about finding costs and market multiples for mineral deposits. My article (Bell, 2015) presents a toy model of the foundational concept in the exploration business, where a speculator pays for costly information to determine whether to invest in a project or not. There is a complex relationship between the exploration spending on the financial statements, exploration results, access to capital, and corporate strategy beyond the scope of this article. This article focuses on key items from the audited financial statements.

The ongoing activity of Kermode continues to present interesting new data to expand the scope of my research. To begin this paper, I show a toy example of a counterfactual simulation using new information regarding the transaction costs for a new property deal compared with the history of all Kermode’s deals going back twenty years. This introduces the concept of what other types of costs could be greater or lower under different regimes, and how they can be modelled using my methods for counterfactual simulation on a time series basis.

Comparing Transaction Costs for New Property Deals

The purpose of this section is to add a new data point to the global public dataset for Kermode. Fascinating because, for the first time, a property deal has attributed legal costs in the deal universe for this article. What happens if we take that new data point for the legal costs of an Ontario property deal and apply it to the universe of all property deals since 2005?

The Q2-2025 interim financials (Kermode Resources Ltd, 2025) provide information on a new data point for an exploration project called Thunder Bay. Described as follows, “The Company issued 15,000,000 common shares (issued at a value of $75,000); and paid other transaction costs of $10,205 related to acquiring the privately held company.” As of April 30, 2025, Kermode had 89,342,966 shares outstanding. It is important to consider property deals in terms of the amount of share dilution they entail, in addition to the dollar value of the shares issued. This type of analysis allows us to investigate questions like when does the acquisition of a new property lead to an increase in equity financing and an increase in exploration spending?

The period from December 2024 to April 2025 was brief in Kermode’s history, but it was characterized by a new board of directors and several changes to the company's financial profile. Although it is less than one year, there are immediate changes in corporate costs, like the rate of directors' and officers' fees. One change is the mention of transaction costs described in this section. Another difference is in the design of the property deal option itself. This deal is structured as a share purchase agreement, where Kermode makes the entire payment in shares, which has a different legal and economic profile compared to an option where Kermode makes staged payments over time. This serves as an example of how the continuous disclosure requirements help provide insights into how a company is changing over time.

Going back to 2005, in all the audited annual financial statements, Kermode does not mention a breakdown of “transaction costs” or legal costs for any exploration projects. The annual statements do show how many deals were coming or going each year, and I believe the number of deals is a fundamental statistic that is important to understand when evaluating a mining exploration company.

The two main regimes in the annual financials are 2005-2020 and 2021-2025. There was different leadership for each regime, which means the data serves as a natural experiment for comparing fundamental aspects of the economic model of the mining exploration company.

2021-2025: New Deals; Abandoned

Total # Deals: 24; -19

Average # Deals per year: 4.8; -3.8

2005-2020: New Deals ; Abandoned

Total # Deals: 5; -5

Average # Deals: 0.3; -0.3

2005-2025: New Deals; Abandoned

Total # Deals: 27; -24

Average # Deals per year: 1.3; -1.1

2004-2020 was the first era in the history of Kermode for this article. This time series illustrates a classic example of the boom-bust cycle in the mining exploration business, as reflected in the financial statements. Exploration spending reached an all-time high for the company around 2007 for a project in Newfoundland (Bell, 2025a), which was capitalized to create an asset on Kermode’s balance sheet. Over time, that asset was impaired as the project’s valuation was seen to be less than the cost of exploration. This is an example of a company learning about a project with costly information and deciding whether to keep it or not, as I described in my model of mineral exploration as a game of chance (Bell, 2015).

2021-2024 was the second era in the history of Kermode. There were major differences in corporate costs, exploration spending, deal flow, and other aspects of financial statements. For example, there are no legal costs attributed to any property deals.

A key example of a counterfactual simulation is based on the legal costs the company would have incurred in the past if it had operated in the same manner as this 2025 comparable. There are important differences in the details of this property deal versus the many others that Kermode entered in prior decades, so it is not a perfect comparison. Although it may not be a perfect comparison, it can be a useful one. It is useful to calibrate important economic parameters based on how different leadership operates with different standards for all aspects of the business and costs.

This counterfactual simulation calculates that Kermode has entered into 24 new property purchase option agreements and abandoned 19 deals since 2021. If we paid $10,000 in legal fees per deal, that would result in an additional $240,000 in corporate costs over 5 years. This is a toy example of a counterfactual simulation. It would be an extra $48,000 per year to add to the Professional fees line item of Kermode’s financial statements, which is a relatively large amount compared to the continued listing requirements.

From 2005 to 2025, Kermode entered 29 new property deals. If paid comparable transaction costs, then an additional $290,000 total over time. It would be an extra $13,810 per year to add to Professional fees.

Modelling Stock Exchange Constraints

In contrast to the flexibility of corporate strategy, there are hard bounds associated with the continued listing requirements from the stock exchange for publicly traded companies. These minimum requirements can serve as constraints for an optimization problem aimed at minimizing corporate overhead costs and maximizing exploration spending.

Here are the continued listing requirements for Kermode Resources:

6 months of working capital on hand at all times

$50,000 exploration spending minimum per year

$100,000 market capitalization minimum

100% increase in the number of shares per year, maximum

The requirements for working capital (1), exploration spending (2), and minimum market capitalization (3) are from the TSX Venture Exchange (2010) publication.

The limit on share dilution (4) is based on the relevant policy for companies when issuing shares below $0.05 (TSX Venture Exchange, 2021). Kermode currently faces (4) as a binding constraint because the shares trade below $0.05. However, it is possible to design a scénario where the company has a higher share price and relax this assumption. This article assumes all requirements are binding when it does an equity financing once each year.

Although the company does not control market capitalization, this toy model assumes that it is under control. Generally, a company wants to avoid the minimum listing requirements. The reason I explore pricing the company at the limit of these requirements is that minimizing the market capitalization provides investors the most significant potential upside return on the back of exploration success. Within the framework of my game theoretic model (Bell, 2015), a lower market capitalization is the same as a lower cost to start the exploration game; a lower cost makes for a greater return in winning scenarios.

I assume the company maintains a $100,000 market capitalization at each round of equity financing on a pre-money basis. I also assume the company raises $100,000 in equity annually. This means the share price must decrease by 50% each year for it to maintain this baseline setup at the limit of the listing requirements (3) and (4).

What does it take for a company to meet the other listing requirements (1) and (2)? This toy model assumes the company spends $50,000 on exploration annually and $50,000 on working capital (auditor fees, transfer agent and filing fees). Are these realistic assumptions?

I am unable to identify the auditor fees from Kermode Resources' financial statements, and this is a potential opportunity for improvement in the way all mining exploration companies provide financial disclosure about their activities. The auditor fees are significant because so many mining exploration companies fail to prepare their annual statements on a timely basis and are subject to failure to file cease trade orders. As such a mission-critical part of corporate costs, companies should disclose the amounts of auditor fees with a detailed breakdown of total costs, paid costs, and unpaid costs every quarter. For example, it would be important for shareholders to know if a company has an unpaid auditor bill that is larger than its cash on hand.

The cost of the audit process depends on the complexity of the company's activities. If a company suddenly has 10 new projects like Kermode, then it is more complicated than a company with one or two projects. The audit costs for Kermode were around $20,000 each year before I became CEO in 2021. For 2024, the audit was around $40,000. The increase in cost is due to higher activity rates for Kermode and general cost increases for audits of mining exploration companies in Canada. It is interesting to note that this increase in audit fees has coincided with a significant rise in the number of companies receiving a failure-to-file cease trade order because they cannot afford to pay for and pass their audit.

I assume the audit fees are $30,000 for the toy model I built to meet the continued listing requirements. I do not have annual time series data for audit fees to compare with this assumption; however, this number represents the midpoint of my costs as CEO of Kermode. It is possible to use this modelling framework to change the audit fees and study the effects on financial performance. Moreover, it would be nice to calibrate this assumption with real data.

Several corporate costs are essential building blocks for a public company—for example, the “Transfer agent and filing fees” from Statements of Loss and Comprehensive. The transfer agent is responsible for keeping track of the shareholder registry, and the filing fees are due to the stock exchange or securities commission. Both are essential. I show how to track them over time and compare them to the number of exploration deals to see how this type of corporate costs varies with the rate of business activity.

For example, the annual sustaining fees for Kermode to the exchange are around $6,500 per year. This fee is calculated as $5,500 plus 0.011% of the Issuer’s Aggregate Market Capitalization. The exchange has additional fees for transactions such as financings, which cost $1,000 plus 0.5% of the gross value of the financing. For a company that raises $100,000 in one financing per year in this toy model, the total fee for the financing would be $1,500 plus GST. It costs $1,500 for the exchange to review any proposed stock option plan. For around $10,000 total, this toy model covers basic fees for the TSX Venture Exchange on an annual basis.

This bare-bones budget for the exchange does not allocate any funds for share issuance towards property purchase option agreements. I am assuming all property deals are generated internally or are structured not to include shares of the company.

Another core cost is the transfer agent. The requirement for the annual shareholder meeting entails costs of mailing in advance and a scrutineer on the day. For example, the cost of meetings for Kermode has ranged from approximately $5,000 for simple meetings and up to $20,000 or more in a contentious meeting. Data can be identified from companies like Kermode on a cross-sectional and time series basis. For the toy model, every year is a smooth and simple shareholder meeting at an ultra-low cost.

The toy model assumes $10,000 for exchange fees, $5,000 for filing fees, and $5,000 for transfer agent fees. For the toy model, the total transfer agent and filing fees are $20,000. How does that assumption compare with time series data from Kermode?

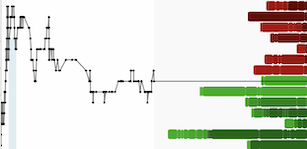

“Transfer agent and filing fees” Kermode Resources Ltd

Average Overall: $20,743

Average 2005-2021 (regime #1): $15,657

Average 2022-2024 (regime #2): $41,089

Based on the long-term history of Kermode Resources, it is clear that the toy model assumption of “Transfer agent and filing fees” equal to $20,000 is a fair assumption for the basic cash costs to operate a mining exploration company that has a low rate of activity.

Furthermore, this data shows that transfer agent and filing fees increase as the company becomes more complicated. This is clearly reflected in the descriptive statistics above. The regime from 2005 to 2020 was a period when the company typically had one project at a time, with turnover occurring every few years. This was a baseline activity rate where transfer agent and filing fees averaged $15,732 per year, directly comparable to the assumptions of the toy model above. The regime from 2021 to 2024 had an elevated rate of activity, and the transfer agent and filing fees more than tripled to $49,142!

Assuming audit fees of $30,000 and transfer agent and filing fees of $20,000, the toy model needs $50,000 for essential corporate overhead costs. This does not allow any cash for officers, directors, consultants, or anyone else. The toy model assumes zero costs to do legal filings with BC Registry and maintain the Registered & Records office. These assumptions meet the constraints (2) for exploration spending within all other constraints.

How did Kermode’s cash spending on corporate costs compare with the toy model? The list of “Operating expenses” from Statements of Loss and Comprehensive Loss provides a list of which costs are included in the corporate overhead total. Then, the “Net cash used in operating activities” from the Statements of Cash Flows shows how much cash was spent on corporate overhead costs, which is comparable to the overhead budget in the toy model.

"Net cash used in operating activities" Kermode Resources Ltd

Average Overall: -$190,081

Average 2021-2024: -$68,074

Average 2005-2020: -$220,583

The average cash spending on corporate costs by Kermode from 2005 to 2025 is almost two hundred thousand dollars, and four times larger than the $50,000 budget from the toy model. However, the 2021-2024 era regime shows average annual cash spending of around $68,000, which is relatively close to the amount in the toy model of $50,000.

Finally, the toy model has a budget of $50,000 for exploration spending. I assume the company has two projects, each with annual holding costs of $15,000. This means that $30,000 must be spent on each project every year, and $20,000 is allocated to the better project. I assume there is no cost associated with generating the projects in terms of cash or shares; the projects can be generated by the internal team of people within the company, or they can be structured as property purchase option agreements with no immediate share payments.

It is unrealistic to assume that officers and directors will work for no compensation, but this is useful as a bare bones demonstration of a mining exploration company that functions according to the limits of the exchange's continued listing requirements. Furthermore, officers and directors can accumulate debts against the company that are not converted to shares or repaid until a future time when the company has better fortunes and is no longer operating at the limit of the listing requirements.

The toy model minimizes market capitalization to maximize the potential upside in the event of exploration success. However, is it possible to have material exploration success on a $50,000 budget? Indeed, it is not enough money to fund the drilling for a new mineral resource estimate! However, a small $50,000 budget may be enough to justify the company obtaining financing at a $1,000,000 market cap, which would provide a 10x return for investors with an original cost base of $100,000. This demonstrates the potential upside return for speculators in this business; however, it is essential to note that the share price must decrease by 50% per year to implement the toy model as a viable business strategy.

This modelling exercise uses the historical range of overhead costs to estimate the required amount of working capital for Kermode Resources because the working capital on the balance sheet was generally negative from 2005 to 2024. I estimate corporate costs required to maintain operations: to ensure the company can pay and pass the annual audit requirements, and maintain all other filing obligations of interim financial statements, so that the company does not become subject to a Failure to File Cease Trade Order.

Discussion

There are opportunities for improvements in the accounting standards for the mining exploration business. For example, report auditor costs on a detailed basis. For example, it would be important for shareholders to know if a company has an unpaid auditor bill that is larger than its cash on hand. The auditor costs are crucial for these mining exploration companies, which have precarious access to capital and rely on their ability to issue shares to fund operations. Additionally, I would like to see companies report exploration activity on a standardized basis, including acquisition costs in cash or equity, as well as exploration costs in terms of prospecting, geophysics, drilling, stripping, and other related activities. Providing standardized reporting across mining exploration companies may allow for better coordination of investment by Mister Market. These companies must agree and adopt relevant non-GAAP methods because the mining exploration is upside down as a loss-making business.

References

Bell, Peter N, 2014. "A Method for Experimental Events that Break Cointegration: Counterfactual Simulation," MPRA Paper 53523, University Library of Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53523/

Bell, Peter N, 2015. "Mineral exploration as a game of chance," MPRA Paper 62159, University Library of Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/62159

Bell, Peter, 2025a. "Financial Ratios for Mining Exploration Public Company Kermode Resources, 2005-2024," MPRA Paper 123791, University Library of Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/123791/

Bell, Peter, 2025b. "Mining Exploration Business Valuation Simulations with Global VMS Database," MPRA Paper 126072, University Library of Munich, Germany. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BgN5AQSI8YGKlyq_1Ds_Y8UrKYcSVfFTohiIcGwdyIk/

Kermode Resources Ltd, 2025. "KERMODE RESOURCES LTD. CONDENSED INTERIM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE THREE MONTHS ENDED JANUARY 31, 2025," SEDAR+. https://www.sedarplus.ca/csa-party/records/document.html?id=df9bceaf405accda05a9b55923b97f14353f19e22a6b3d8151495003e7756527

TSX Venture Exchange, 2010. “POLICY 2.5: CONTINUED LISTING REQUIREMENTS AND INTER-TIER MOVEMENT,” https://www.tsx.com/en/resource/425

TSX Venture Exchange, 2021. “Notice to Issuers: Re: Temporary Relief of $0.05 Minimum Pricing Requirement – Further Extension,” https://www.tsx.com/en/resource/2776

TSX Venture Exchange, 2023. “POLICY 1.3: SCHEDULE OF FEES,” https://www.tsx.com/en/resource/2937/