By: Tekoa Da Silva

Tekoa Da Silva: Rick I'd like to ask you today about the decade of the 1970s.

During the decade of the 1970s U.S. President Richard Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard. There were bouts of wage and price controls, gasoline rationing, an oil embargo and political turbulence.

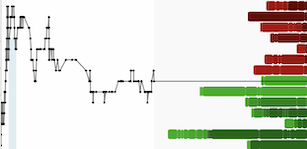

From 1970 to 1980 the price of oil went from roughly $1.21 bbl to about $40.00 bbl. Gold went from $35.00 oz. to over $800.00 oz., and the CRB commodity index moved up about 300% during the decade.

Rick in terms of where you were at the beginning of the decade - I understand you graduated high school in 1971. You started college at the University of British Columbia, and you were contemplating a career at that point in natural resources tax law, is that right?

Rick Rule: That's correct. Mercifully I was saved from a career in law by a lawyer who told me that I would be unhappy with it. But the rest of it's all correct.

TD: While you were in college you entered into the hospitality business and became acquainted with some of the “Living Legends” of the Vancouver Venture Exchange, and with your hospitality business you were able to develop a quite a rapport with some of these “Living Legends”. Can you talk about that experience?

RR: That's also true. I immigrated to Canada, and I had to have a job to get through school and the only marketable skill I had, was that I was a very large aggressive young man who had spent ten years boxing.

So my initial employment was as a bouncer, so I could work at night and go to school during the day.

Through one mistake after another, I came to own establishments rather than just working in them, and one particular establishment I owned became the chief watering hole for all the people who went on to make the Vancouver Stock Exchange what it was.

I need to say Tekoa that while my university education was around natural resource finance, I learned the intricacies of natural resource finance better serving alcohol to the people who were involved in doing it, than I did in college courses.

In retrospect, it makes sense that a tenured professor who was an academic would know less about the thrust and parry of finance then the people who were working every day in finance.

But I am delighted that my hospitality career both furnished the capital to go into the extractive industries, but much more importantly furnished me the knowledge that allowed me to be successful over the next 50 years.

TD: Rick in 1974 you started investor relations activities for resource companies, and in 1976 you became a full-time resource investor. This happened in the market context of 1974 - as you recall there was about a 30% decline in the Toronto Stock Exchange and about a 40% decline in the S&P 500.

The large American energy companies Exxon and Chevron participated in the decline despite the much higher oil prices. Did that decline impact your area of the resource market and did it create fertile ground in any way for your investment activities?

RR: It absolutely positively created fertile ground.

In the early part of the decade of the 1970s gold - but in particular - gold stocks were on fire. There was no particular need to translate rather complex natural resource stories into actionable ideas for investors because the market was doing it for them.

Beginning in 1974 the Fed tried to raise interest rates and the consequence of raising those interest rates was that a broad range of commodity stocks and other stocks declined precipitously in price.

It was the turmoil caused by those price declines that allowed me to work with people that became really truly legendary resource financiers. In particular Adolf Lundin - he would have had no use or no need for me in 1970-1972.

But by 1974, Adolph Lundin had a couple of companies in his stable and attracting investors was nowhere near as easy as it had been in the years before.

So in truth, it was understanding that a one or two year decline wasn't going to derail the resource thesis - in other words having the courage to participate. And the market itself, having a need for my participation, meant that I was extremely lucky in the period.

TD: In 1971 Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard. Was there popular discussion of that topic at the time? And how do you interpret that event in retrospect?

RR: The stage was set for that in 1965-1967. The country was coming off a 20 year equity bull market. The period from 1946 to 1966 was 20 years of unalloyed American glory - lower interest rates, low inflation, and American hegemony. Yes, the cold war was there, but it was really a period of American hegemony.

With that, came American hubris. We decided to fight a war in Vietnam and a war on poverty simultaneously. You're too young to know this, but we lost both.

What we were left with at the end of the decade of the 1960s were fairly high marginal tax rates and unserviceable debt and deficits. What Nixon did – and remember he took foreigners off the gold standard. It was U.S. President Roosevelt who had taken Americans off the gold standard much earlier. Roosevelt knew he couldn't pass his counterfeit paper on to us if there was an alternative.

So Nixon took foreigners off the gold standard, but prior to that you could exchange U.S. dollars for gold if you were a foreigner. Foreigners, and in particular Charles de Gaulle, looked at the out of control U.S. deficits, government spending and entitlements. Rather than hold euro dollars, he preferred to exchange them for gold. Nixon looked at De Gaulle’s actions and said, “Hmm, how can we perpetrate fraud with a knowledgeable counterparty?”, and closed the gold window.

So the closing of the gold window wasn’t something that happened overnight. He did it in the context of uncontrollable strains on the U.S. Dollar. What it also did was clarify the financial circumstance of the U.S.

Even to a high school student like myself in the 1960s, the hallmarks of inflation were present. I wasn't an economics student, but I was smart enough to notice the price of a hamburger at McDonald's go from $.20 to $.80, and gasoline from $.20 to $1.00 a gallon.

Perhaps because I didn't have much money the impact of inflation on my purchasing power struck me much harder and made me more aware of it. But for the American public coming off 20 pretty good years, it took a while for the impact of inflation to become extreme enough, for Americans to take note.

I would suggest it wasn't until late 1971 to 1972 that the length and breadth of the American citizenry became aware of the really pernicious impact of inflation on their lifestyles. I think what Nixon did, while it didn't directly impact Americans, it served as an icon that the circumstance of American economic culture of the preceding 20 years, was gone.

TD: In late 1973 OPEC nations increased the oil price and Arab OPEC members announced an oil embargo on the U.S.

A barrel of crude oil moved in price from about US $2.00 bbl at the beginning of 1973 to about $13.00 bbl in early 1974.

In the U.S. there was rationing and shortages of gasoline for passenger cars and many drivers were waiting in line all day for gas. In early 1974 commercial truckers went on strike nationwide demanding a rollback in gas prices. Fist fights occurred at gas stations and some striking truckers fought with non-striking truckers.

It was a tense environment to say the least. This occurred when you were in college. How do you recall the social environment at the time?

RR: Well, one of the reasons I left the U.S. and went to Canada was the social environment. If you dial back again to the 1960s, going to school in California where I lived, involved needing a gas mask to get the class.

I left the turmoil of the U.S. because of the Vietnam War and other social issues, and went to Canada, to the University of British Columbia, which was an engineering school and extremely quiet.

So a lot of the drama that happened in the U.S. wasn't visited on me in Canada. Canada was at that point in time, and still is a petroleum exporting country. Canada also maintained adequate supplies of oil and gas during the period that you described, and enjoyed frankly a boost in the national economy as a consequence of their efficiency as oil producers.

A few things strike me about the circumstance that you describe. The first is that the cure for low prices is always low prices. The extraordinarily low prices that the oil industry received in the period 1963 to 1970, and the incredible flood as an example, of oil that came out of the Persian Gulf - those low prices discouraged production in other parts of the world.

It was really those low prices that enabled the hegemony of foreign producers. The low prices squeezed inefficient producers out of the market. That allowed the efficient producers to engineer the embargo.

In the later part of that decade when the oil price went above $30.00 bbl, U.S. and other national consumers began to conserve and substitute other materials for oil. At the same time they encouraged a flood of new production.

So I think the first thing to take away from an investor standpoint, is that the cure for low prices is always low prices and the cure for high prices is always high prices.

The other thing that's striking about that period is the sense that the citizenry, exemplified in this case by the truckers, thought that the government was bigger than the market. The idea that the truckers advocated a rollback in energy prices - I have been struck through my entire adult life at the response of the citizenry to government's ability to do anything other than interfere with markets and make things worse.

What did the truckers exactly believe that the U.S. was going to do? Perhaps they were advocating U.S. invading Saudi Arabia. I have no idea what they had in mind, but the truth was that the diesel price - save government as an example foregoing sales tax, which I don't think would ever happen - was something absolutely beyond their control. The faith in government exhibited by Americans is at once touching and maddening.

TD: Rick in the late 1970s, commodity prices continued to escalate. What did you do as a resource investor to take advantage of the situation?

RR: Sadly Tekoa, I made two amazing mistakes during the decade of the 1970s.

As you know, I began the decade as a 17-18 year old guy with massive ambition and no financial means. As a consequence of being in natural resource-based businesses for that decade, I came out of the decade an extremely wealthy young man. Two bad things happened.

The first is that I conflated a bull market with brains. I thought the increase in my net worth through the decade of the 1970s had something to do with my skill, conveniently omitting the fact that the gold price had gone from $35.00 oz. to $850.00 oz., and the oil price had gone from less than $2.00 bbl to over $30.00 bbl.

When the oil price collapsed in 1982, I learned just how smart I was, which is to say not very. I think the lesson I didn't understand at the time, is that markets work.

If you dial back to 1977-1978 and looked at all the commodity price forecasts issued by the so-called reputable bodies - OPEC, The Royal Bank of Canada, The Club of Rome - there was truly a Malthusian aspect to expected resource pricing. I remember popular wisdom believed we were going to run out of food and there was going to be mass starvation of 30-40 million people a year by 2000. The oil price was supposed to be $200.00 bbl by the year 2000.

All this Malthusian thinking around natural resources was very convenient to a young man who was in the natural resource business. By all conventional thinking I thought I was going to be a blue eyed sheik. That's how my banker described me at that point in time.

When the projections of The Club of Rome are looked at today, they become farcical. Food became cheaper and much more abundant. The price of oil collapsed from a high of $40.00 bbl all the way down to $12.00 bbl. The price of decontrolled natural gas declined from $15.00 mmbtu to $.70-$.80 mmbtu.

At the time I decided also that debt was a cheaper form of capital than equity for some of my activities, so not to dilute my ownership interest. I learned a lot about credit too. I found out that the value of my assets was ephemeral - an oil well is worth a lot less at $12.00 bbl than at $35.00 bbl. But my debts were all money good, meaning, that I had to pay off debt at 100 cents on the dollar.

So it was an interesting and very painful circumstance for me. But I learned a lot and the lessons I learned were that markets work. I also learned that you are a product of your circumstance. You're a product of your effort too.

I learned a lot about the responsible use of credit and how to organize your own personal finances. But all the things that led to my downfall were also responsible for the successes I've enjoyed since.

I should say one other thing, which is that in 1982 my net worth went negative. But I decided not to go broke, and got my principal creditors together and told them that if they cooperated with each other and didn't jump each other in the credit line, that I would do my level best to work myself out of the situation and pay them all back, principal and interest. It took me four and a half years, but I was able to do it and that had two major beneficial consequences for me.

The first was self-esteem, I did what I said I was going to do, which made me feel better about myself. The second thing is that people who participated in the project, which is to say the people who I owed money to, and the community that they influenced - became my best backers over the next two decades of my life.

So that was an important lesson I learned at the time, that if you do the right thing and you communicate correctly – what is on the face of it, a very ugly situation, can be used to your advantage

TD: Rick was that circumstance a stock portfolio with margin lending? Or was it a private entity that you put together to accumulate oil wells?

RR: I didn't have any margin lending on securities, what I had was a couple of advances to other parties who defaulted, and in particular I had a private oil and gas business that was funded both on carried working interests from selling participations to other parties and my own direct investments.

I also had a revolving credit facility, and the revolving facility restated in terms of its borrowing base every year, depending on the beginning oil and gas prices of the year. So you can have a large credit facility at $35.00 bbl and no credit facility whatsoever at $20.00 bbl, which is what happened to me.

In addition to oil and gas assets, I had a couple receivables. One of the receivables was from a broker-dealer operation in the U.S. Midwest that went broke. Although I wasn't the largest creditor to that broker-dealer operation, I was certainly the creditor whose debt comprised the largest proportion of his net worth. The consequence of that, was the other creditors elected me to go work that circumstance out with, first of all, disproportionate benefit to my interest and a performance bonus.

I was able to do it, and in the course of about a year's hard work, liquidated that broker-dealer. And while I didn't return all the capital to shareholders or creditors of the broker-dealer, I distributed substantially more capital than they would have been able to receive without my efforts. I was well compensated for that, and that activity was an integral part of my digging myself out of the hole I had dug for myself.

TD: Rick, you've developed a wonderful reputation as a financier in the natural resource exploration space. Did you start exploration finance after that credit experience, or was it during or prior?

RR: During and prior. I've always had a real fascination for exploration and science. Being in Canada in the decade of the 1970s and being involved in assisting in the financing of several successful exploration endeavors during that decade was very exciting. Exploration finance is a fascination that's never left me.

I also enjoy complex topics. I enjoy being involved in problem solving where there are lots of variables, and that really describes exploration. I like businesses where the distribution of information is inefficient or hard to understand, and where the harder you work, the more competitive advantage you generate relative to your counterparties.

And again, that describes exploration. What I didn't realize at the time Tekoa, was that in the 1970s I was building what was then called your ‘Rolodex,’ now called your contacts. I did my first transaction with Adolf Lundin in 1974, and I would say that my relationship with the Lundin’s has been my most important business relationship over the ensuing 50 years. I went to university with Ross Beatty, who went on to found 14 successful mining companies in the ensuing 50 years.

I became acquainted with Chester Miller, rest in peace, who was also an extraordinarily successful mining engineer and mining explorationist. The period from 1974-1985, in addition to giving me some operating experience, gave me a wonderful range of contacts. Contacts I could invest with, contacts I could ask questions of, and truly, I need to say that by 1990, I had all the contacts that I needed for a successful career.

I've often thought, frankly, that if I hadn't done business with anybody after 1990, whom I hadn't met and done business with before 1990, that I would have worked a quarter as hard and made twice as much money.

Pareto's law works well in most forms of business, and I had the good fortune in my first 10-15 years in the mining and oil and gas business to meet 10-15 serially successful natural resource entrepreneurs. Developing relationships with them, developing trust with and in them, and developing the ability to understand how they think and how to participate in their successes but avoid their failures is something that served me extremely well since.

TD: Rick, in 1980-1981 many commodity prices peaked. There was also a peak, as you recall, in the Fed funds rate, which exceeded 19%. What do you recall from that period as being some of the most extreme events and behaviors that you saw around you?

RR: My own behavior is one example. When the prime rate went from 11.00% to 19.00%, the writing should have been on the wall to me. With as much debt as I had, the debt service was going to be a much more serious issue, and it would alter investor behavior. If you were taking risk for a 25.00% internal rate of return, when you could get a riskless 19.00% and do no work whatsoever - it should have occurred to me that capital would flow from risky activities to riskless activities. In other words, that capital would flow from oil and gas drilling to the US 10-year treasury.

That's what happened, but sadly it took place without me. On the other side of the circumstance, the upside blowout in resources, if you haven't experienced it before, is extremely seductive. You work for a decade around a paradigm of resource scarcity. You work for a decade around The Club of Rome Malthusian discussions of resources, and this incredible move to the upside is merely vindication of what you already believe.

If you don't go into the experience with the historical lesson that the cure for high prices is high prices, what happens is that the move in prices appears to you to be the logical outcome of the narrative that you bought into 10 years before. That's what happened to me, so I missed the upside blowout in its entirety, for which I have myself to blame.

TD: Rick, I think you've answered this question in bits and pieces here throughout the conversation so far, but in reflecting on the 1970s decade as a whole - what were the main educational lessons that you took from that experience?

RR: First of all, markets work. The cure for low prices is low prices. The cure for high prices is high prices. Never forget that. Learn to love hate. At the beginning of that decade, commodity prices were low because commodities had underperformed other asset classes for 20 years. The fact that other asset classes had outperformed and were arguably, at least with regards to the Nifty 50, overpriced didn't occur to people precisely because they had outperformed. That outperformance had numbed people to the risks they were running.

With regards to natural resources, the fact that they had been cheap for 20 years meant investors thought they were always going to be cheap. Forgetting of course, that the cure for low prices is low prices.

It was the experience of the fact that markets work that enabled me in 1998 and then again in 2022 to participate early and aggressively in both uranium booms, which made an enormous difference in my net worth. It was the same lesson that allowed me to understand that during COVID when the oil price briefly fell to being negative, and when Exxon got kicked out of the Dow 30, that these were one-off events. A recovery both in the oil price and in Exxon was inevitable.

Those are lessons that came about as a consequence of experiencing the decade of the 1970s. The second lesson, which unfortunately took me longer to learn, is that the most important part of finance is time.

You need to invest in a way where time is on your side so you benefit from compounding. That's not what you want, particularly as a young man. As a young man, you want your thesis to be validated before the next long weekend, and you want to make money quickly, and you think that what you want matters to somebody other than you, but it doesn't.

When I look back at the successes I enjoyed in the decade of the 1970s and the successes I've enjoyed since - the greatest successes, the ones that changed my net worth and my reputation, took 5-8 years. Time has to be on your side.

The third thing is that people matter a lot. If you look at the distribution of success in natural resource finance, and I would suggest probably to other realms of life, what you learn is that a truly disproportionate amount of the success is enjoyed by a relatively few people. The 80/20 principle, as it's commonly known, or Pareto's Law, suggests that 20% of the population generates 80% of the positive utility in any given task. And less well known is that there is a different 20% that generates 80% of the disutility or aggravation.

What you learn is that if the task and population base is large enough, you can run either of those 20% lips through the same performance dispersal curve, and they conformably align - which is a fancy way of saying that 20% of the 20% do 80% of the 80%, or 4% of the population generates 64% of the utility. And I think you can run the same performance dispersal curve at least one more time, which is to suggest that a tenth of 1% of the population, or to make the math simple, 1% of the population generates 40% of the utility.

What that means is that if you hang out as an investor with the serially successful, while you will miss a couple of newcomers, statistically the importance of those newcomers is insignificant. If you invest continually and faithfully, and for the long term with the best of the best, you will statistically have the highest probability of good outcomes.

TD: Rick, some of these notable events we saw in the 1970s (embargos, currency depreciation, etc.) and the experiences you had in that cycle - do you think Westerners and Americans in particular, will see some of those events again?

RR: I don't know. I can give you some broad observations though. The first is that pessimism, real pessimism, is futile. We will, 20 years from now, be better off than we are today. When I look at everything wrong with the U.S., as an example, I still look at a culture where five or six young, pimply-faced kids can take over a garage in Sunnyvale, California, and out pops Apple or Google.

The truth is, with fits and starts, our individual creativity and tenacity has thus far always been able to fund our collective stupidity. There have been times where that's been a challenge, but we've done it.

The second thing is that the world is much bigger and much more inclusive. I don't mean to sound politically correct, but that garage doesn't need to be in Sunnyvale anymore. It might be in Lagos, Chongqing, or Jakarta. And that's a very good thing. It means the U.S. doesn't have to carry the world anymore. There will be a time, I think, when the world carries the U.S.

The bad news is that political solutions to private problems are increasingly popular in the world, including in the U.S. And the arithmetic that confronts Americans is substantially worse than it was in 1970. In 1970, you had a young workforce just coming into their savings and investment years, the so-called baby boomers. You had many more working people than you had beneficiaries for public programs.

The madness of public programs, however thoughtfully conceived, was affordable at the time. The circumstance is very different now. We have a lot of retired people, and a lot of people sucking on the system and not so many people contributing to it.

So the arithmetic overall isn't pretty. The on-balance sheet liabilities of the U.S. government before state, local, and agency debts, exceed $34 trillion. That is a substantial premium to annual GDP. But the scarier number is the net present value of the off-balance sheet liabilities - Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, military and government pensions. That number, according to the Congressional Budget Office, exceeds $100 trillion.

So the balance sheet of the federal government is $120-$130 trillion upside down. And we're trying to pay off this debt, including the debt to each other, with a budget that adds to the unfunded current liabilities to the extent of $1 trillion dollars every 100 days. This is truly unsustainable.

I suspect the way we get out of it is that we begin to means test benefits - to reduce in a real sense, benefits, and also that we age test Social Security. But the real way we get out of it is we inflate away the obligations, the same way that we did in the 1970s.

Remember, in the beginning of our discussion, we suggested that between the war on poverty and the war in Vietnam, strange parallels to today – that the value of our obligations was greater than our political will to service the debt. And the way we did it is we inflated away the purchasing power of the US dollar.

We devalued the US dollar surreptitiously by 85% over the decade of the 1970s. And I think the only way out of $130 trillion in liabilities - while we're adding to that number by at least $3 trillion a year before the accrual of Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, is that we inflate away the net present value.

That means people your age, if they're thinking about a retirement that includes Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, you better think again. My generation voted ourselves all kinds of cool benefits, but we forgot to pay for them. We left you the bill. While I apologize for that, the solutions you dream up for yourself are going to have to involve funding yourself.

People need to take into account the twin problems of society coming to depend less on entitlements and government, at the same time private wealth experiencing challenges due to inflation. People who don't understand that vice compression for the next 10 years, I think are in for a real surprise. There's going to be a real ugly price to pay.

TD: Rick, how can our readers follow your work?

RR: Well, the easiest way if they care about natural resources is to go to my website, RuleInvestmentMedia.com. List your natural resource stocks, and for no obligation and no charge, I'll personally rank them. 1 being best, 10 being worst. I'll comment on individual issues if I think my comments have any value.

For people who care about being active investors, by all means, go to our boot camps. We have online eight-hour-long symposiums four times a year with deep dives into various aspects of investing.

TD: Rick, thank you for sharing some of your life experience with us today.

RR: A pleasure, Tekoa. I hope it saves some of your readers some of the scars that I’ve earned in the latter part of the 1970s and the early part of the 1980s. And I hope it contributes to their success.

To reach the author, Tekoa Da Silva, visit: x.com/TekoaDasilva