Of the roughly 2,250+ listed companies on the Canadian venture exchanges, which are among the most active startup stock exchanges in the world, approximately 5%, if not less, are profitable. Most companies on the Venture exchanges (TSX-V; CSE) are very early-stage startups rather than true growth opportunities.

This tends to mean that their ongoing operations are dependent on raising capital, in an environment where terms are at the mercy of market volatility and trendy (spotty) demand. This is not a new dynamic of capital markets and isn’t expected to change any time soon. Public venture markets are a match-making environment of pairing companies with risk-takers.

In this article I will attempt to help investors and companies seeking their next financing understand the true costs associated with a private placement (the most common financing structure for Canadian Venture-listed companies).

Experiencing both sides of raising capital has helped me understand the complexities of the situation. On one side, there’s the risk taker, who invests his capital seeking a return. On the other side, there’s the Company, which is looking for investment to continue growing.

It’s a delicate balance, and at first I didn’t spend much time trying to understand the implications from a Company’s perspective. But an understanding of what happens inside a Company when they’re trying to raise capital in the public markets can also help investors understand what to watch for, or watch out for, when a company they are invested in is raising money. A company financing can tell investors a lot about management, the company’s existing investor base and the general investor appetite for the company or its industry.

Breaking Down the Cost of Raising Capital:

Let’s start with what is often most easily understood, the numbers.

Expense and fee structures for each private placement are unique, but roughly follow some guide as below:

- *$1M Private Placement example

- Legal - $25-50K

- Broker Cash Fees - 5-10% of total dollars raised

- *Broker Warrants - 5-10% of total dollars raised

- *Other finders fees (including corporate advisory fees) – up to 10% of total dollars raised

- *Warrants - Half or Full Warrant

- $1M less ($25K + $100K) = $875K

At first glance the net costs of $875K from roughly $1M aren’t so bad. However, while I’d love to imagine raising capital was this easy and transparent - unless management or the board of directors has sufficient capital markets experience, or the Company has a bonafide sponsor, many companies end up going down a different path. Let me share with you, more commonly, how private placement transactions proceed.

Some examples of hidden costs not included:

- Pre finance marketing - $10K- $50K

- Post finance marketing - $200K

- *Cheque Swap for Marketing - $100K

- *Overhang of stock - $Priceless

- $875K less ($250K) = $625K

After including a relatively small marketing budget of $250K, the gross proceeds after all costs are $625K for management to re-invest in the business. Remember, it costs roughly $200K per year for a public company to operate, given exchange fees, lawyers, accountants and miscellaneous public fees, which leaves a relatively small amount left for the business.

Why does marketing have to be included?

It’s typical to include some type of marketing costs, whether it be hard cash or a cheque swap (which is when a Company pays for a service with a cheque and the service provider then gives a cheque back to the Company to participate in the private placement), because this is how the brokers or sponsors typically protect their investment.

A broker’s primary incentive is collecting fees, which in this scenario is based on the total dollars raised. Therefore, while focused on raising capital to pay themselves, brokers also need to maintain their clients’ snowball of cash. The broker’s true investment is turning over their clients’ cash to repeat the process with another company.

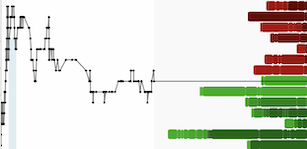

On any private placement there's a statutory 4-month hold period, where the private placement participants are restricted from selling shares. There’s something called a “Discounted Market Price”, which means the market price less the following maximum discounts based on closing price:

Up to $0.50 / 25%

$0.51 to $2.00 / 20%

Above $2.00 / 15%

Generally, most private placements are done at a discount (20%-25%) to market which aids in soliciting the stock because it now seems cheaper and therefore more attractive to the investor. Especially if the open market price is still trading at higher prices than the discounted terms. The tradeoff of having an opportunity to purchase shares at a discounted market price is why the 4-month escrow policy was imposed. (This discount should be viewed as another form of “expense” the existing shareholders will bear.)

This is where the marketing expense is key.

As the restriction date approaches, the marketing budget is spent to create new interest in the Company. The hope is there’s enough open market buying for the private placement participants to sell their stock in the open market.

This is especially true if the Company has included some type of sweetener in the form of a full or half warrant. When a warrant is attached to the private placement, it provides the investor additional upside even after selling their shares. Once the private placement participants have sold their stock, the broker then has his capital back to repeat the same process with another Company.

Attracting long-term shareholders is the real-challenge

I’d argue that while the cheap injection of capital can be extremely important, as much weight should be placed on where the money comes from. Focusing on finding investors that understand the business, support the long-term interests of the company and have a history of doing so, is far more important than just raising a few bucks. Having investors that understand the business can be much more valuable than 100 small traders that want to clip the warrant and sell at first opportunity.

What tends to happen is that companies misunderstand the highest cost of the capital raising process, which is eliminating the future potential to gain long-term shareholders. Companies must not be naive about this. They must understand that it’s quite possible the entire $1M of capital raised is eventually going to be sold back into the market. Which may work out well if the Company never needs to refinance, but it only makes the next round that much more difficult, given the increasing supply of sellers challenged by a further depressed share price.

Depending on the discount to market, the Company could be trading $1M (for e.g. $1.2M at 20% discount) worth of stock (*plus warrants) for $600K of hard cash (*or even less if there’s a cheque swap), which hardly seems like it’s in the best interest of shareholders. In that same process, the Company wasted money on marketing, diluted their shareholders, eliminated an opportunity to create long-term shareholders, squandered precious time and exposed their brand. Most importantly, the Company created an entire legacy of new issues moving forward. Chiefly, how to find $1M of open market buying to patch the looming sell-off, but this time with $0 in the marketing budget.

Advice for investors

For the investor, it’s important to know the business you’re invested in, but it’s just as important to know who your business partners are. When you invest, you’re also investing in your partners. I'm talking about the other shareholders - understanding their intentions and potential problems they can create.

Ask yourself, do you know who is the lead order on the financing? Where is the Company raising money from? How much are they being compensated? Who are the other placees? And is there a cheque swap or some type of marketing program underway?

The less sophisticated a Company or its management team is, or depending on how desperate they are, can make this process even more costly. All of the broker fees, finder’s fees and quality of investors can come at steep costs, and even worse, companies can be duped into egregious cheque swap schemes. Just take a look at the Bridgemark scandal, which sent ripples through the Canadian micro-cap ecosystem as it damaged companies, investors and continues to taint the marketplace.

Advice for Companies

If you’re raising capital and not thinking about, or looking at these things, you should be.

Think about who your investors are and what type of investors you want to attract. You’re entering a minefield and you will want authentic support.

When it comes to strategy, here’s how I would do it. Bypass the brokers. Spend more time finding a single lead order, a strategic investor or family office. Put the effort into seeking quality investors. It’s a game of quality over quantity.

Meeting brokers and expecting them to raise capital comes with strings attached and is likely not going to be helpful long-term. Why not offer the 25%/20%/15% discount to a quality investor or family office who can spend the time to understand the business and patiently support the Company? I’d argue there is more value in this approach as opposed to adding low quality investors that don’t support the Company’s long-term vision.

In addition, if you’ve never raised capital before, it’s of paramount importance that you find a vested capital market advisor to help navigate these challenges. In fact, I’d argue that all companies need a capital markets advisor that owns stock, thinks long-term and is not focused on collecting fees. Even better, find a board member who’d be willing to chair this role.

Conclusion

If you are an investor that connects with management, this might give you some insight into why they are reluctant to speak to you, or have limited interest in hearing your thoughts on strategy. Many companies fall prey to this perpetual game of dilution and turn their backs on Howe Street, Bay Street and even Wall Street. Don’t be alarmed if management shells up and focuses on what it knows best, their business.

As for companies and management, you may think you’re benefiting by getting the capital you currently need, but if you have a significant ownership you may be doing yourself a disservice. Be sure of who you are entering into a business partnership with and tread carefully.

For all parties, be wary, be skeptical, ask questions, and if you don’t know the answers - seek those who have experience that you can trust.

Trevor is a Vancouver based micro-cap investor and writer.